Defining a Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC)

A special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) is a company that does not conduct any kind of regular business and is founded only for the purpose of issuing shares to the public in order to acquire or merge with another firm.

SPACs, which are sometimes referred to as "blank check firms," have been around for quite some time, but have seen a huge increase in popularity in recent years. There were 247 new SPACs formed in 2020, with $80 billion invested, and a record 613 SPAC IPOs in 2021. Only 59 SPACs made their debut this year.

How do they work?

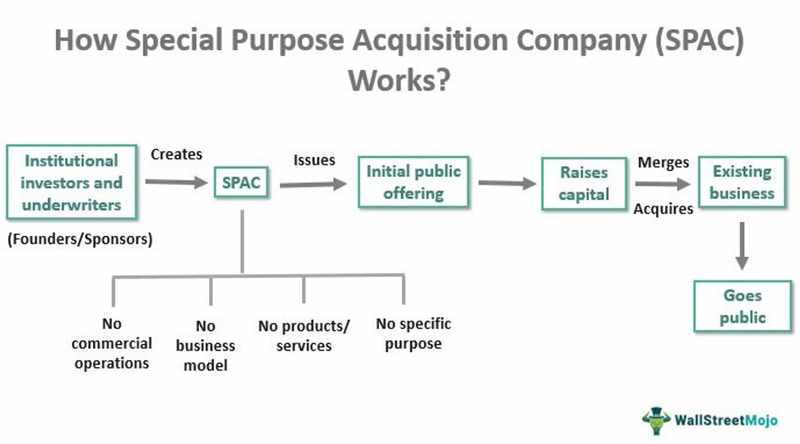

Investors and sponsors with experience in a specific field often form SPACs to focus on transactions in that area. During the IPO process, the founders of a SPAC may be trying to avoid disclosing details about any potential acquisitions they may have in mind.

SPACs are often referred to as "blank check corporations" because they give IPO investors very little information. Before offering their shares to the general public, SPACs go to underwriters and institutional investors. Goldman Sachs, Credit Suisse, and Deutsche Bank were among the notable institutions and retired or semi-retired employees who flocked to SPACs during their boom years of 2020 and 2021.

SPACs deposit their IPO proceeds into a trust account that earns interest but from which they are prohibited to be withdrawn unless used to make an acquisition. If an acquisition cannot be made, investors' money will be returned and the SPAC will be liquidated.

Any SPAC that has an unfinished transaction after two years must be liquidated. The SPAC can use the trust's interest income as operating capital in particular situations. SPACs are typically listed on a major stock exchange after making an acquisition.

The $13.6 billion that was raised through SPAC IPOs in 2019 was a record high. They raised more than four times as much as they did in 2016, which was $3.5 billion. The years 2020 and 2021 saw a rise in the popularity of SPACs, with a combined total of up to $162.5 billion raised in 2020 and $83.4 billion in 2021. By March 13, 2022, SPACs had collected $9.6 billion.

Going back to its origin

When special purpose acquisition corporations (SPACs) originally emerged as blank-check corporations in the 1980s, they were not effectively regulated, leading to a proliferation of penny-stock fraud that cost investors over $2 billion annually by the early 1990s. Congress stepped in to provide much-needed regulation, such as mandating the use of regulated escrow accounts to hold the proceeds of blank-check IPOs until mergers are finalized. Following the implementation of new regulations, "blank check" companies became known as "SPACs."

Due to their popularity in the decades that followed, SPACs spawned a cottage industry consisting of specialized businesses such as law companies, auditing firms, and investment banks that provided services to SPAC sponsors who otherwise lacked professional experience in public and private investing. Reflecting the available investment options, they concentrated on troubled businesses or specialized sectors. However, in 2020, a large number of SPACs were launched by serious investors. An abundance of cash, a rise in the number of startups looking for either liquidity or growth capital, and regulatory improvements that standardized SPAC products all converged to make SPACs attractive to a wide range of investors.

The current gold rush may be traced back to the credibility and competence offered to the market by these seasoned players. Overall, however, the credibility of modern SPAC sponsors is higher than ever before, which has led to an increase in the quality of the targets they pursue and a corresponding boost in investment returns.

The majority of SPACs today invest in businesses that are shaking up the consumer goods, IT, or biotech industries. Some of these businesses are highly risky, need massive upfront funding, and provide few guarantees of success in the near future. (This is a common classification for electric vehicle manufacturers.) In order to fuel innovation across sectors, several companies have turned to SPACs to obtain capital. Although inexperienced investors should avoid risk and speculation at this level, we think that skilled analysts can identify promising investment opportunities.

However, not everyone is convinced, and that includes the aforementioned researchers. Their research, published in the Yale Journal on Regulation, centered around a key aspect of contemporary SPACs: the ability of investors to back out of a merger after a target has been identified and announced by the sponsor. Investors who are unsatisfied with the terms of the deal can opt out by redeeming their shares for the original amount they paid plus any interest accrued. It was determined by the study's authors that the median redemption rate for the SPACs they examined was 73%, with an average redemption rate of 58%. Furthermore, almost 90% of investors abandoned more than a third of SPACs.

At first glance, those figures don't look promising, as they seem to indicate that most SPAC investors are withdrawing their support once targets have been identified. Closer inspection of the data, however, revealed that many SPACs had raised below-average capital and offered above-average warrants to lure investors, both of which are signs of less-than-stellar sponsor teams. In the previous nine months, both the market and sponsor teams have undergone significant shifts and improvements. Consequently, there has been a dramatic decrease in the number of investors pulling their money. When we looked at redemption rates after the research concluded, we discovered that. The average redemption for the 70 SPACs that hit their mark between July 2020 and March 2021 was only 24%, or just 20% of the total capital invested. Over 80% of SPACs had redemptions of less than 5%.

This shows that the risks, stakeholders, structures, and performance of the current SPAC ecosystem are materially different from those of the ecosystem that existed as recently as 2019. As part of this new ecosystem, corporate boards, investors, and entrepreneurs are working to simplify the SPAC process and make it as adaptable as possible, all with the goal of improving the economic proposition for target companies by maximizing their current valuation, long-term opportunity, and risk.

SPAC advantages

Companies that have been thinking about going public can benefit from SPACs. While the traditional IPO procedure can take six months to more than a year, the SPAC route to public offering may just take a few months.

With such a short window to initiate a deal, the target company's owners may be able to negotiate a higher price when selling to a SPAC. The target company has access to seasoned management and increased market exposure through an acquisition or merger with a SPAC sponsored by famous financiers and business executives.

It's possible that the global pandemic of 2020 sparked the rise of SPACs since many companies opted out of traditional IPOs due to unpredictable market conditions.

Risks associated with SPAC

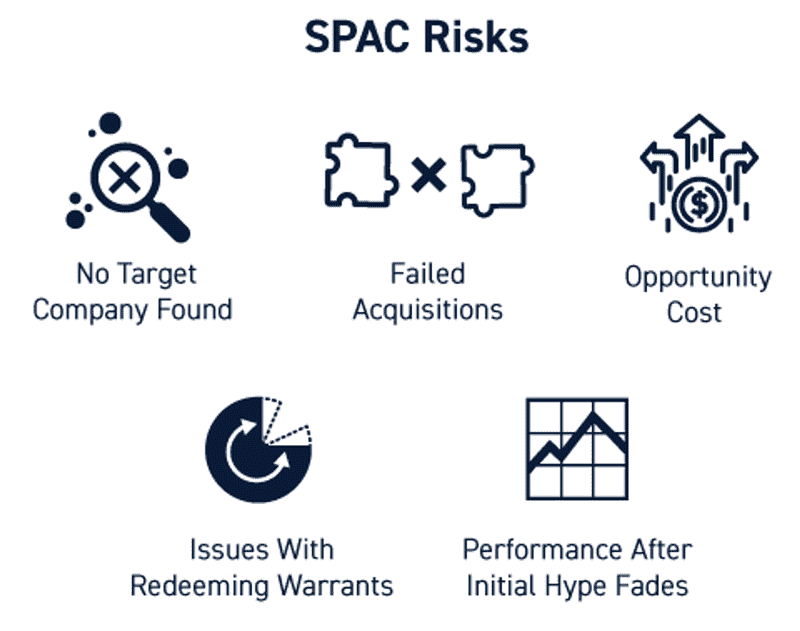

To put it another way, an investor in a SPAC IPO is betting that the promoters will be able to successfully acquire or merge with a suitable target firm in the near future. However, because of a lack of information from the SPAC and lax regulation, retail investors run the danger that their money may be mismanaged or stolen due to the investment's inflated claims.

Subpar Returns

There is a chance that SPAC returns will fall short of those promised during the promotion phase. In September 2021, Goldman Sachs strategists observed that the median SPAC had beaten the Russell 3000 index from its IPO through transaction announcement, out of the 172 SPACs that had closed a deal since the beginning of 2020. In contrast, the median SPAC underperformed the Russell 3000 index by 42% in the six months following the deal close.

One Renaissance Capital strategist estimates that by the end of 2021, as many as 70% of SPACs that had their IPO that year were trading at less than their $10 offer price. Some market experts have speculated that this negative pattern indicates the SPAC bubble may be breaking.

Digital World Acquisition Corp., a special purpose acquisition company, released Donald Trump's conservative "Truth Social" app to the public (DWAC). The price of DWAC stock skyrocketed to approximately $100 per share after the deal was announced in the spring of 2022, but by the year's end, it had fallen precipitously to around $20.

Unfulfilled Deals

Investing in a SPAC carries the risk that the firm may not be able to complete the acquisition of the target company. Industry reports indicate that in 2022, more than 55 purported SPAC partnerships with a total value in the tens of billions of dollars were scrapped, and an additional 65 SPAC sponsors went out of business.

There are a number of potential roadblocks that could cause a SPAC transaction to fall through. The SPAC may be unable to locate an appropriate acquisition target in time, for example. If the SPAC's management team is unable to locate a private firm that meets the investment requirements described in the SPAC's prospectus, or if the private company declines to be purchased by the SPAC, the SPAC may be unable to fulfill its acquisition objective. It's also possible that the SPAC's management won't be able to strike a good bargain on the deal's essentials, such as the purchase price or the structure of the arrangement. Another potential problem is that the SPAC doesn't make enough money from the IPO to pay for the acquisition. This may occur if there is insufficient demand for the SPAC among investors or if the market is adverse. Last but not least, the acquisition must be approved by the SPAC's shareholders and the relevant authorities before the deal can be considered a success.

Investors in SPACs usually receive a return equal to the par value of their shares ($10.00 per share), but may incur losses if they purchase shares at a premium in anticipation of a deal concluding. Investors are not entitled to the market price at which SPAC shares are purchased, but only to their proportionate share of the trust account.

Scam Alerts

New SPAC filings dropped dramatically from record highs in the first quarter of 2021 due to new accounting standards imposed by the Securities and Exchange Commission in April 2021.

In March 2021, the SEC published an "Investor Alert" warning investors not to base their investment decisions on the involvement of celebrities, including actors, musicians, and athletes.

Due to higher levels of regulation and weaker-than-anticipated returns, SPACs fell out of favor by early 2022.

SPAC stakeholders

There are three key parties involved in SPACs: the promoters, the investors, and the intended beneficiaries. They are all different and have their own worries, requirements, and points of view.

Sponsors

Initiation of the SPAC procedure falls on the shoulders of the sponsors. They finance their operations with risk capital in the form of nonrefundable payments to bankers, attorneys, and accountants. If the SPAC's sponsors are unable to forge a merger within two years, the SPAC must be disbanded and the investors' money returned. Not only do the backers lose their own money and time, but they also lose any potential return on their risk capital. However, if they are successful, the sponsors will give them equity in the new company equal to as much as 20% of the capital they initially raised.

Come on, let's crunch some numbers. An initial $6–$8 million is put into a SPAC by its sponsor to cover overhead expenses like underwriting, legal, and due diligence work for an intended $250 million in the capital. SPAC raises $25,000,000 through the sale of 25,000,000 shares at $10 each. The sponsor additionally acquires 6,250,000 shares (20% of the total outstanding shares) for a nominal price. The founders' shares will vest at $10 per share, for a total value of $62.5 million, if the sponsors are able to complete a merger within two years.

Investors

Institutional investors, typically highly specialized hedge funds, have made the vast bulk of SPAC investments thus far. Investors in a SPAC's IPO have to put their faith in the company's sponsors, who are not required to stick to the size, valuation, industry, or geographic criteria they established in the offering's initial public offering paperwork. Common stock is issued to investors at a price of $10 per share, and warrants are issued at a price of $11.50 per share, allowing the holder to purchase common stock at a later date. The risk-alignment arrangement between SPAC sponsors and investors relies heavily on warrants. Some SPACs issue one warrant for every share of common stock purchased; others issue fractions (typically half or one-third of a warrant per share); and still others issue no warrants at all. Incentives to subscribe, such as warrants, which offer early investors a chance at the further upside, correlate inversely with the perceived risk of the SPAC because more warrants indicate a bigger potential for loss.

Following the sponsor's announcement of an agreement with a target, the original investors have the option of proceeding with the deal or withdrawing, with the latter resulting in a return of their initial investment plus interest. They can preserve their warrants even if they opt to withdraw. To that end, the SPAC gives them a chance to learn about private companies without taking any of the usual risks associated with such investments.

Targets

SPACs typically invest in newly formed companies that have already secured venture funding. Firms at this juncture often weigh their options, which may include going public through an IPO, going public through a direct IPO listing, selling the business to another company or a private equity firm, or raising additional capital from private equity firms, hedge funds, or other institutional investors. As an alternative to these choices in the late stages, SPACs can be very appealing. As a result of their adaptability, they can be tailored to meet the needs of a wide range of possible permutations. Even though most targets are single private companies, sponsors can use this framework to acquire many targets at once. Companies that are already publicly traded in other countries can be taken public in the United States using SPACs, and numerous SPACs can be merged into a single SPAC to go public.

FAQ

What are some real-world examples of SPACs?

Particularly notable among deals employing SPANs was Richard Branson's Virgin Galactic. To prepare for its 2019 public offering, venture capitalist Chamath Palihapitiya's SPAC Social Capital Hedosophia Holdings purchased a 49% interest in Virgin Galactic for $800 million.

On July 22, 2020, Pershing Square Capital Management was founded by Bill Ackman, who also sponsored the largest SPAC to date, Pershing Square Tontine Holdings, which raised $4 billion. Ackman had originally planned to liquidate the SPAC in August 2021, but as of 2022, attempts were still ongoing to find a deal.

How can you invest in SPACs?

SPACs allow the public to 'partner' with investment experts and venture capital firms in order to gain access to the private markets, where most ordinary investors are unable to engage in potential privately held enterprises. There are now exchange-traded funds (ETFs) that invest in special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs), with the portfolios of these funds often including a mix of firms that have recently gone public through a merger with a SPAC and SPACs that are currently looking for a target to take public. The level of risk associated with an investment in a SPAC will vary, as it does with any investment, based on the particulars of the deal at hand.

Which companies went public through SPAC?

Digital sports entertainment and gaming platform DraftKings, aerospace, and space travel company Virgin Galactic, energy storage innovation leader QuantumScape, and real estate marketplace Opendoor Technologies are just some of the well-known companies that have gone public by merging with SPAC.

What happens if a SPAC doesn’t merge?

There is a deadline by which a SPAC must complete a merger with another company. This time period typically lasts between 18 and 24 months. If a SPAC is unable to complete a merger within the prescribed time frame, it is required to dissolve and return all investor money.

Does a SPAC have certain criteria?

The normal time frame for a SPAC to execute an acquisition is 18 to 24 months, and at least 80% of its net assets must be used for the purchase. If it doesn't, it has to dissolve. When a SPAC is dissolved, the assets are distributed to the investors based on their proportionate ownership.