Defining an institutional investor

A business or organization that manages investments on behalf of others is known as an institutional investor. Examples include insurance firms, mutual funds, and pension plans. The whales on Wall Street are institutional investors because they frequently buy and sell enormous blocks of stocks, bonds, or other securities.

Additionally, the group is thought to be more knowledgeable than the typical retail investor, and in some cases, they are subject to less onerous rules.

How do they operate?

On behalf of its clients, customers, members, or shareholders, an institutional investor purchases, sells and manages stocks, bonds, and other financial assets. Endowment funds, commercial banks, mutual funds, hedge funds, pension funds, and insurance companies are the six main categories of institutional investors. Because it is assumed that institutional investors are more aware and better able to defend themselves than average investors, institutional investors are subject to fewer protective rules than average investors.

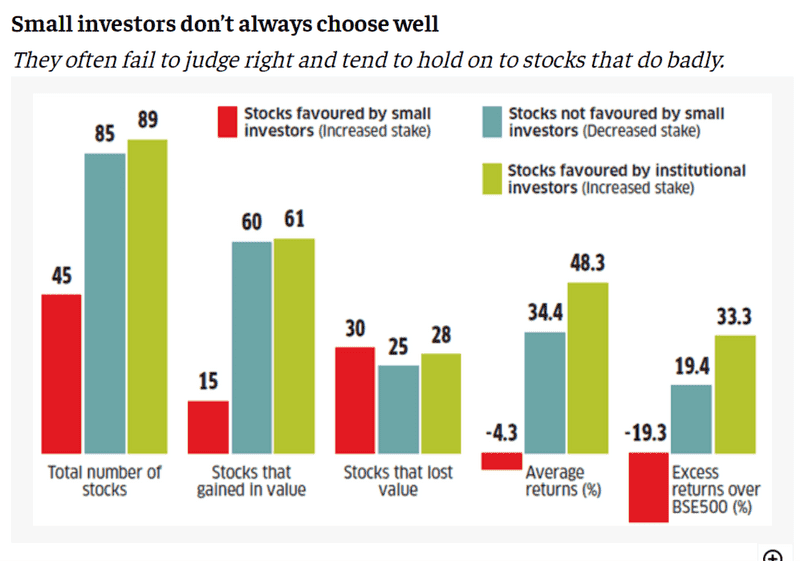

Retail investors lack the resources and specialized knowledge needed to conduct in-depth research on the range of investment alternatives available to institutional investors. Institutions perform a substantial percentage of transactions on major exchanges and have a significant impact on the values of securities since they move the largest positions and are the largest force behind supply and demand in securities markets. In reality, more than 90% of all stock trading now is conducted by institutions.

Retail investors frequently investigate institutional investors' regulatory filings with the Stocks and Exchange Commission (SEC) to ascertain which securities they should buy directly because institutional investors have the power to impact markets. To put it another way, some investors try to imitate institutional buyers' purchases by adopting the same positions as the so-called "smart money."

The various types of institutional investors

Institutional investors come in a variety of forms on the market. They each specialize in asset classes and use unique investment approaches.

Hedge funds

One of the most well-known categories of institutional investors in the financial sector is hedge funds. Blackrock, AQR Capital Management, and Bridgewater Associate are a few of the largest hedge funds in the world. A hedge fund's primary goal is to "hedge" against losses in the entire stock market, as the name implies. By holding both long and short positions on different securities, this is frequently accomplished.

Hedge funds normally do not accept subscriptions from retail investors and have tight standards for their investors. You must be an Accredited Investor in order to invest with a hedge fund.

Illiquidity is one distinguishing feature of investments made through hedge funds. As a result, hedge fund investors are forced to hold onto their investment for a longer amount of time without having the option to cash it in or sell it. Additionally, hedge funds frequently employ a concentrated investment strategy in which money is allocated to a small number of assets in disproportionately large amounts, making it more vulnerable to larger gains and losses. Hedge funds are therefore viewed as a riskier investment.

Mutual funds

Another typical investing vehicle is a mutual fund. Stocks, bonds, funds, and other securities may be included in a mutual fund's underlying investments. The majority of mutual funds invest in easily traded liquid equities. Some of the most well-known mutual fund managers in the world are Vanguard, JP Morgan, and Fidelity Investments.

Mutual funds are well-diversified investments that span a variety of markets, sectors, and businesses. Through diversification, they are intended to reduce the risk of capital losses for their investors. Most mutual funds do not have minimum investment criteria and are accessible to the individual or retail investors with only a little initial investment. Mutual funds have several appealing qualities, including minimal entry barriers, a lower risk profile, and suitability for novice investors.

Private equity and venture capital

Institutions that invest in private companies that aren't publicly traded are known as private equity ("PE") funds. The investment is frequently illiquid since its duration—which is normally over five years—is so long. Due to the high minimum investment amount, PE institutions typically exclusively target high-net-worth individuals as their client base, and they are able to offer investors access to private companies that are unnoticed.

A type of private equity financing known as venture capital (VC) often offers finance for start-ups, early-stage businesses, and developing enterprises with strong development potential. A VC's normal goal is to make early investments in startups with the intention of raising their valuation through a series of funding rounds, with the ultimate goal of an initial public offering (IPO). Sequoia Capital, Softbank, and Andreessen Horowitz are a few well-known venture capital firms that have backed successful startups like Facebook, Airbnb, and Über, to name a few. Investments in PE and VC are regarded as high-risk.

An insurance provider

The insurance plans that an insurance company sells, which are often classified into life and non-life insurance policies, need regular premium payments from its customers. A portion of the premiums collected is often invested in the long term to produce returns and pay claims. These companies invest in a variety of financial products, such as government bonds, long-duration bonds, and inflation-hedged bills.

Prudential PLC, Allianz SE, and Axa S.A. Insurance are a few of the biggest insurance providers in the globe.

Endowment funds

Universities, hospitals, charity foundations, and other non-profit organizations sometimes create endowment funds to manage their finances, which are normally derived from donations and are not required right away. Typically, beneficiaries' activities, such as offering scholarships or funding charitable events, are to be funded with money from investment operations.

Pension funds

Pension funds are funds created with financial aid from pension schemes. As the main objective of pension funds is to provide steady financial income for pensioners upon retirement, the collected cash is often distributed to investments that generate income and are financially secure.

Pension funds often only invest in well-diversified funds, low-risk government bonds, large-cap equities, and stable real estate assets since they have low-risk appetites. The Central Provident Fund (CPF) in Singapore, the Government Pension Fund of Norway, and the California State Teachers Retirement System are a few well-known examples of pension funds.

Understanding the impact of institutional investors

Market maker

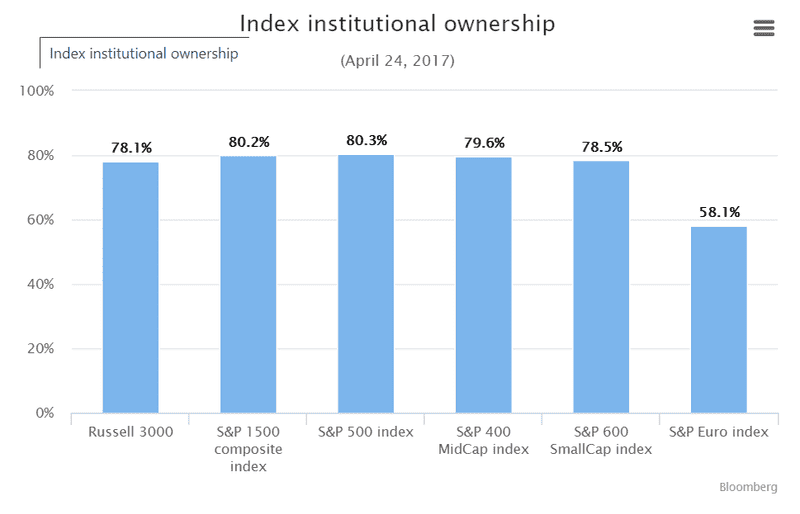

The financial market gives institutional investors a lot of sways, and they can have a big impact on how specific securities' prices move. They also hold sizable stakes in businesses that are publicly traded. A Harvard Business Review analysis found that institutional investors hold about 80% of the stocks in the S&P 500 index; this holding is valued at about $21.7 trillion USD. Additionally, financial organizations like State Street, Blackrock, and Vanguard are the three biggest owners of the majority of the Dow 30 firms.

Financial markets rely heavily on institutional investors since they finance companies and provide liquidity for the financial assets they trade. Additionally, by enhancing managerial transparency and price discovery, they contribute to increased market efficiency.

Corporate governance

Institutional investors provide economic contributions as well as actively participate in enhancing corporate governance standards. A research report by UCLA Business Law Professor Stephen Bainbridge claims that because institutional investors make far larger financial commitments than ordinary investors, they have more incentives to become experts at tracking and monitoring their assets. This practice has pushed businesses to operate under the guidelines of good corporate governance.

Additionally, institutional investors that own a sizable amount of the stock have more clout to hold the management of corporations accountable for activities that jeopardize the interests and welfare of shareholders. When a company's performance declines, institutional investors are able to make beneficial changes to the board's makeup since they own a sizable number of the company's shares and voting rights.

In other words, institutional investors give their invested companies more than just money; they also offer advice, networks, and support that can be helpful.

Benefits of institutional investors

1) Lower fees

Institutional investors typically trade on high-volume shares and only partake in huge transactions, which are defined as block trades involving at least 10,000 shares and a sizeable amount of capital. This gives them the ability to bargain for lower transaction costs and better terms on their assets thanks to their scale and purchasing power. Institutional investors might not additionally be subject to fees like marketing or distribution costs.

2) Access to securities

Access to unique investment opportunities is available to institutional investors. These deals could need a lot of money, like commercial real estate, money, or futures contracts, which are normally out of reach for regular investors.

Other transactions, like initial public offerings (IPOs), futures, and swaps, are only available to institutional investors due to their complexity and high level of risk. Institutional investors are thought to have the skills, background, and capacity to protect themselves from hazards. Institutional investors may purchase private placements in the United States under Rule 506 of Regulation D as Accredited Investors. Co-investing, however, also gives individual or retail investors access to special investment opportunities. For instance, co-investing in real estate enables regular investors to participate in institutional real estate prospects.

3) Resources and professional guidance

Institutional fund managers are typically seasoned investing professionals. Compared to individual investors, these experienced managers are less prone to feeling greed or fear while making investments. One of the main causes of retail investors losing money is emotion. Additionally, institutional investors have access to more sophisticated technology and analytical tools, which enables them to do more precise financial analyses while evaluating their investment possibilities.

Institutional investors vs. Retail investors

Markets like bonds, options, commodities, currencies, futures contracts, and stocks are just a few of the ones where retail and institutional investors are involved. However, some markets are more for institutional investors than ordinary investors due to the structure of the assets and the way transactions take place. The swaps and forward markets are examples of marketplaces that cater primarily to institutional investors.

Institutional investors are known to engage in block trades of 10,000 shares or more, whereas retail investors are known to buy and sell stocks in round lots of 100 shares or more

Institutional investors occasionally refrain from purchasing stocks of smaller companies due to the bigger trade volumes and sizes for two reasons. First, buying or selling significant quantities of a tiny, thinly traded stock may cause a rapid imbalance in supply and demand that will cause share prices to rise or fall.

Additionally, institutional investors often steer clear of owning a sizable stake in a firm because doing so might be against the law. For instance, the percentage of voting securities that mutual funds, closed-end funds, and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) that are registered as diversified funds may own is constrained.

Institutional Investor | Retail Investor | |

Funds | Enormous amounts of pooled money belong to the companies and organizations in which it invests | Limited to the amount an individual can allocate for trading and investing |

Potential Trading Impact | Large positions and frequent transactions can result in sudden price movements that are unexpected by other investors and can move an entire market in unexpected directions | Typically, smaller trade sizes and less frequent trading has little adverse effect on market movement |

Emotional Trading | Less of an issue due to investment and market experience and expertise, education, and instant access to feedback and advice | May occur due to a lack of investment education and readily available market feedback; can have a positive or negative impact on markets if substantial trading occurs by enough individuals |

Transaction Type/Size Example | Block trades of 10,000 shares or more | Round lots of 100 shares or more |

Protective Regulations | Subject to less protective regulation due to investment expertise and knowledge | Subject to more protective regulation due to perceived experience, education |

Limits | Not likely to limit buying to any particular size of company or share price level | More likely to invest in stocks of companies with lower share prices to enable more purchases for diversification |

Information Advantage | Access to extensive market research and up-to-the-minute market insight and specialist feedback | Access to a wealth of information has less access to the information reserved for institutional investors |

Understanding the risks of institutional investment

You run the following risks when dealing with institutional investors:

- Too much money: Unusual as it may appear, many institutions manage an excessive amount of money. They are unable to purchase smaller stocks and may even cause larger stocks to influence the market. They lack the freedom of an individual investor and must be very careful where they invest.

- The risk associated with active management: The majority of institutions use the recommendations of managers to invest money actively, as opposed to passively (as was stated above with regard to ETFs).

- Fees: Fees can ruin any investment. Institutional investors charge commissions that might be anything between 0.1% and 50% of the earnings made. Wall Street knows how to structure agreements to ensure that it gets paid — regardless of returns — but no approach is infallible.

The investing markets

Even with the aforementioned concerns in mind, institutional investors are still crucial to the market. Without them, it genuinely wouldn't exist. Market makers boost liquidity and reduce transaction costs on every highly traded exchange.

Let's imagine, for illustration, that you want to purchase Nike stock. When you place the order with your broker, it is most likely carried out right away. That isn't because you accidentally placed the order at the same time as someone else who conveniently wishes to sell the same number of shares. Due to a market maker who approved the trade. On the market, market makers trade shares all day long. They purchase shares from one party and immediately sell them to another. They make money from the bid/ask to spread instead of seeking to profit from the trades.

You get paid the stock's bid price when you sell it. You pay the asking price when you purchase. These are typically only a few cents apart, if at all. Each day, market makers process potentially millions of transactions and set the spread. More market makers will compete for shares with more trading volume, which reduces the bid/ask spread. The spread is bigger for equities that are more infrequently traded, but it is still worthwhile because you might not be able to buy without it.

In summary

The big fish on Wall Street, institutional investors have the power to influence markets through their enormous block trades. The group is frequently subject to less regulatory supervision and is generally thought to be more sophisticated than the retail crowd. Institutional investors typically don't invest their own funds; instead, they choose investments on behalf of shareholders, clients, or other stakeholders.

FAQ

How do institutional investors make their money?

Returns from investments do not immediately benefit institutional investors because they invest on behalf of other people. These investors are compensated for managing investments through asset management fees or by receiving a cut in profits if the investments meet certain performance benchmarks.

Are family offices considered institutional investors?

Similar to institutional investors, family offices invest and manage assets on behalf of the families they represent. They do not manage investments from other people, unlike institutional investors, and often only manage investments for one client, which is the family they represent.

What is the % of investors that are institutional?

It is difficult to estimate the total number of actual, active investors, both institutional and retail. On the New York Stock Exchange, institutional investors are known to account for more than 85% of the trading volume.

What is the definition of a retail fund?

An investment fund created with the small-scale investor in mind is known as a retail fund. A mutual fund or exchange-traded fund is an example of a retail fund. Institutional investors are not the primary target market for retail funds' investing options. They transact in a free market. Frequently, they don't require a minimum balance but may do so with high maintenance costs (compared to those charged by institutional funds).

Are institutional investors important?

Financial markets rely heavily on institutional investors since they finance companies and provide liquidity for the financial assets they trade. Additionally, by enhancing managerial transparency and price discovery, they contribute to increased market efficiency.